Lubec: A Border Town Shaped by the Sea

Text by Jennifer Multhopp

With images from Lubec Memorial Library, Lubec Historical Society, Edith Comstock Collection, Lubec Landmarks and Susie Calder.

Map of Cobscook Bay Area, 1881

Lubec Memorial Library

Lubec’s connection to the sea and its close proximity to the Canadian Maritimes have shaped its destiny – from trade and fishing in the early years, through the prosperous era of herring processing, and into the present with efforts to forge economic recovery through aquaculture and tourism. From its earliest settlement the town has maintained ties of family, friendship and commerce with New Brunswick.

Early Settlement

With its 95 miles of shoreline, fresh and tidal wetlands, and waters teeming with herring, pollock and shellfish the area drew its earliest inhabitants, members of the Passamaquoddy tribe, who made seasonal encampments at Seward’s Neck (North Lubec) during the spring smelt run, gathered sweet grass and harvested shellfish, the remains of which have been discovered in shell middens along the shores of Mill Creek and South Bay. The very word “Passamaquoddy” means “pollock plenty place” in the tribal language.

Colonel John Allan's cenotaph, Treat's Island, 1970

Lubec Memorial Library

Later settlers included Acadians, forced to flee Nova Scotia, veterans of the American Revolution, and those like Colonel John Allan and Louis Delesdernier who sought refuge after being exiled from the provinces by the British due to their support of the War for Independence. In 1777 Allan was received by the new Congress and appointed Superintendent of the Eastern Indians, a post he held for the remainder of the war. He was credited with having secured the neutrality of the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy and Micmac Indians despite British efforts to enlist their support against the Americans. After the war he settled on Allan’s Island (Treat’s Island) where he operated a trading post.

Louis Delesdernier was eventually appointed the first Customs Collector for the District of Passamaquoddy by George Washington. With the end of the war in 1783 and formation of the federal government efforts were made to control trade in the region. The border between the U.S. and New Brunswick remained ill-defined and settlers who had long enjoyed free trade with their neighbors in the provinces were unwilling to pay duty and adhere to restrictions imposed by the new government. Delesdernier was eventually ousted from his position due to his inability to control trade. Later customs officers Lemuel Trescott and Hopley Yeaton fared no better.

Solomon Cushing Survey of North Lubec, 1795This is a reproduction of the survey of North Lubec, Plantation #8, made by Solomon Cushing in April, 1795. It is the earliest map of North Lubec, known as Soward's Neck at that time. Cushing was a surveyor sent to the area from Massachusetts to lay out 100-acre lots which were later assigned to settlers upon payment of $5 to cover the survey's cost. This reproduction of the original map was drawn by Lois Johnson and first appeared in "200 Years of Lubec History, 1776 - 1976".

Incorporation

Conditions around Passamaquoddy Bay were quite primitive at that time with dense forest extending to the water’s edge, few houses, the only roads being foot and horse paths. Travel was by boat. By 1790 North Lubec, with a population of 245, was far more developed than Flagg’s Point (Lubec). John Cooper, acting as agent for the settlers, petitioned the Massachusetts General Court declaring allegiance to that state and requesting that settlers’ land holdings be legalized.

The petition included the following reasons for seeking incorporation: “That their situation exposes them to difficulties which no other part of the State labors under; on the one hand harassed by the British and commanded to bear a part in the administration of their affairs being (as they say) within their jurisdiction; on the other hand obliged to pay obedience to the laws of Massachusetts …. declared to be within the limits of their government.” The petition was accepted and an official survey completed with 100-acre lots assigned to North Lubec settlers upon payment of $5 to cover the cost.

Lubec, North Lubec and Moose Island were incorporated as the town of Eastport (Plantation 8) in 1798 with 588 inhabitants. Lubec remained part of Eastport until June 21, 1811 when, as a result of a successful petition presented to the Massachusetts legislature, it became incorporated as the 188th town in Maine. “Lubeck” as it was spelled in the Act of Incorporation, included Dudley, Frederic, Mark and Rogers Islands. It was reported that Jonathan Weston suggested the name for one of the German free cities because of its shape, location and the fact that trading was as “free” as anywhere in the country. A warrant for the first Town Meeting was issued on July 7, 1811.

Hopley Yeaton grave, North Lubec, ca. 1960

Lubec Memorial Library

Smuggling

During this period, despite measures taken by Washington to curtail illicit trade in the border region, goods continued to flow freely between the U.S. and British provinces. In 1790 President Washington organized the Revenue Cutter Service (later to become the United States Coast Guard), commissioning Hopley Yeaton as its first officer. Yeaton, America’s first commissioned naval officer, was sent to the Passamaquoddy region, charged with curtailing the growth of smuggling there. He settled in North Lubec where he spent the rest of his life.

In 1807 President Jefferson initiated an embargo on overseas shipping which only served to further anger border communities. American vessels were forbidden to trade with foreign markets, causing economic hardship in Lubec and Eastport. Local resistance to the embargo was fierce and the widespread smuggling of flour, salt beef, and other goods into British territory became increasingly difficult to combat. Fishermen, well acquainted with area waters and tides, isolated coves and islands; as well as the close proximity to Campobello and Deer Islands made the work of customs officials difficult indeed. In addition, the lack of a firm border agreement with the British until 1818 and the government’s inconsistent policies also fostered illegal trade.

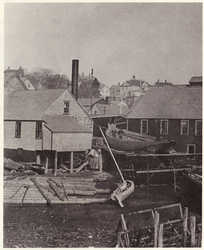

John McBride Shipyard, LubecThe John McBride Shipyard, located on Water Street, launched a number of schooners and barkentines in the 1860s and '70s. Among them were the Lizzie B. McNichol, Minnie Hunter, Annie Gillise and the Nellie Dinsmore. Photo by Frank P. Adams.

Schooner Charles E. Sears, Lubec, ca. 1900

Lubec Memorial Library

Lubec’s connection to the sea also offered ideal conditions for the rise of ship-building, with 20 vessels launched from town shipyards between 1804 and 1830. The first schooner, Hope, was built in North Lubec by Captain George W. Allan. The growth of this industry brought increased prosperity to area farmers, who harvested the timber, and to blacksmiths, carpenters, ship-chandlers and other suppliers of materials needed to construct the yards and vessels.

Prosperity

Eastport was captured and occupied by the British from 1814 until 1818 when the boundary dispute with the U.S. was finally settled, establishing the border between Canada and the U.S.; Campobello and Lubec. During the occupation Jabez Mowry and several other prominent Eastport merchants who had long profited through their smuggling activities, came under increased scrutiny by the British who sought payment of customs duties. Mowry and the others relocated to Lubec where they re-established their businesses; cleared trees; built dwellings, wharves and stores; and returned to the pursuit of their lucrative border trade. Their defection was a boon to Lubec as Mowry, who remained in the town, helped establish the first post office, church, schoolhouse and meeting hall, later entering local politics.

Cleaves Tavern, Lubec, 1955

Lubec Memorial Library

Lubec’s center of population began to shift from North Lubec to the Point. Campobello was only a few hundred yards away and it was very profitable to bring in British merchandise at a low price and sell it here. The population had grown to 1,430 by 1820. Contraband trade flourished with Campobello where wharves full of British manufactured goods were exchanged for cash, beef, pork, flour and wood products. The town entered a period of growth and prosperity and in 1820, the year that Maine separated from Massachusetts to become the 23rd state, the road from Lubec to Machias was completed and William Chaloner established a stage coach run connecting the two towns. The inn that offered accommodations to passengers arriving in Lubec still stands today on Pleasant Street.

Herring being transported, Lubec, ca. 1930

Lubec Memorial Library

Early Industry

At this time there were 20 smokehouses in Lubec producing 50 to 60 thousand boxes of fish annually, bringing employment and prosperity to the town. In 1797, Daniel Ramsdell cured the first herring by smoke, a process of preserving fish he had learned in Nova Scotia. Lubec would become the national leader in smoked herring production. Smokehouses and the many brush weirs that supplied herring lined the shore. Weir construction also brought a measure of prosperity to area farmers who cut the necessary stakes and brush needed to build and refurbish the herring traps. So great was the demand for the large herring preferred by the smokehouses that Lubec began sending vessels to the Magdelen Islands in the quest for fish. The 1855 Maine Register reported: “During the 1850s it was said that the smoked herring business employed every male resident over the age of 10 in the Washington County town of Lubec.”

Lubec’s 20-foot tides were harnessed to power plaster and grist mills. The Gazetteer of Maine, 1882 reported: “The tide power privilege available at North Lubec is equaled by very few on the entire coast. The site would be highly advantageous to any manufacturer seeking cheap and abundant power. The tide rises about 20 feet in Lubec and with suitable arrangement of canals and reservoirs furnishes the most reliable, consistent and cheapest kind of water power.” George Comstock established the first mill at Mill Creek. Flour produced by his grist mill helped provide a more varied diet for area residents. In 1832 a canal connecting Johnson Bay and South Bay was dug and plaster mills constructed where Jeremiah Fowler employed 125 men. Plaster was a highly sought commodity used to lime farm fields and finish interior walls. The gypsum and grinding stones to supply the mills were among the goods smuggled into the country from Nova Scotia. In 1898 Lubec’s tidal power and isolated location led to the birth of another industry – The Electrolytic Marine Salts Company, "Klondike” -- the gold from seawater hoax.

Ferry Lubec at Dock, Lubec, ca. 1935

Lubec Memorial Library

Due to increases in retail activity, fishing and fish processing employment opportunities, shipping and farming, Lubec’s population grew to 3,000 by 1850. The town boasted three post offices, four churches, several fraternal organizations including Freemasons, and a ferry connecting Lubec and Eastport. People migrated to the town in search of work and, with money to spend, shopped at the growing number of stores on Water Street. Lead mines were dug in West Lubec and on South Bay.

War and Trade

In the midst of prosperity came the outbreak of Civil War and, in 1861, over 200 men aged 18 to 40 entered the Union Army – one for every 12 inhabitants. On December 14, 1862, Albion K.P. Avery was killed in action at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Lubec’s first war casualty. By the end of the war 14 soldiers had been wounded, with 26 killed in battle or having died in hospital. A monument honoring Lubec’s Civil War veterans, as well as those of subsequent wars, was dedicated on September 20, 1904.

Original copy of the Soldier's Monument Dedication Souvenir Program

Following the war Lubec’s smoked herring industry began a gradual decline. The war had a negative impact on the business, causing interruptions of shipments to customers in the south. In addition, the industry suffered from over production, decreasing prices, and the shortage of large herring. At its height there were 45 weirs operating in town with 500,000 boxes of herring smoked annually. By 1879 many of the 74 smokehouses were idle. This decline did not last and by 1900 the industry had revived.

Carrying Place Cove, Life Saving Station, Lubec, ca. 1890

Lubec Memorial Library

Schooner Whitebelle Wreck, Lubec, 1931

Lubec Memorial Library

Growing trade and markets led to an increase in ship traffic and the need for improved navigational aids. In 1806 Hopley Yeaton petitioned President Jefferson to establish West Quoddy Head Light and in 1809 it was completed with Thomas Dexter as the first keeper. The Lubec Channel Light was commissioned in 1890. Shipwrecks led to the construction of a lifesaving station at Carrying Place Cove in 1874. A log kept by the light keeper at West Quoddy Head recorded as many as 17 outbound and 15 inbound craft passing the Head in September 1874. Incoming cargo included coal and flour from Boston, as well as sugar, molasses, rum, guano, coffee, fruit and spices from the West Indies. Exports were salt and smoked fish, sardines, potatoes, hay, wood and other agricultural products.

By 1880 the era of sail had given way to the rise of steam powered vessels. A group of businessmen formed a committee to build wharves that would accommodate the new ships. On August 31, 1893 the S.S. Cumberland, captained by William Allen, became the first steamship to carry passengers from Boston to Lubec, arriving to great fanfare. Upon docking, it was heralded as “the first landing of a passenger and freight steamer from the outside world.”

Columbian Canning Company Smokehouse Employees, Lubec, ca. 1900

Lubec Historical Society

Sardine Industry

Julius Wolff, a food broker from New York, arrived on the shores of Passamaquoddy Bay in 1875 attracted by the abundance of small herring. In 1870 the Franco Prussian war interrupted the importation of sardines to America and importers in New York began searching for another source of the food, so popular with growing numbers of European immigrants arriving in U.S. cities. The birth of the sardine industry brought an unprecedented era of economic growth to the region.

Lawrence Cannery Camps, North Lubec, 1955

Lubec Memorial Library

In 1880 Moses P. Lawrence, Henry Dodge and Julius Wolff established a sardine factory in North Lubec, built on the site of a former plaster mill on the canal. It was called The Lubec Packing Company, the first among scores of factories that would eventually line Lubec’s waterfront. Soon thereafter E.W. Brown and Company built the first factory on Water Street. The next two decades saw 23 sardine factories constructed in Lubec, bringing employment and more retail businesses to support the growing needs of employees and their families.

Lawrence Packing Co., North Lubec, 1936

Lubec Memorial Library

Entire families, including children, found work processing sardines. During the season workers came from Campobello, Grand Manan, Deer Island, and towns throughout Washington County, many living in rows of company houses built by factory owners. Men gathered the herring from weirs, transported them to the factories, cooked the sardines and sealed the cans. Until child labor laws were instituted in the 1930s children, using sharp knives, removed the heads, tails and entrails from the fish. Women sorted, added any condiments and packed the sardines into cans. Each factory would sound its own distinctive whistle to alert workers that there were fish to be processed.

Sardine packers, Lubec, ca. 1976

Lubec Memorial Library

Edith Comstock, R.J. Peacock Canning Co., Lubec, 1980

Lubec Memorial Library

Edith Comstock, a life-long resident of North Lubec, began packing sardines in 1931 when she was 14 years old. “Herring choker was the nickname given to the women who packed sardines,” she recalled. “The herring, being pre-cooked, were soft, so when we packed the small fish in cans, eight or more per can, we just snipped the head off between our thumb and forefinger, as though choking them. That’s how we got our nickname.”

Women and children were paid by the piece, up to $3 a day in the early years. Wages and working conditions improved as the industry grew. More on canning sardines in Lubec.

Rise and Fall

Lubec’s population rose to 3,363 by 1910. American Can Company built a plant for the manufacture of two-piece, drawn cans, employing hundreds of workers. Business flourished with drug stores, grocers, hotels, department stores, a movie theater, bowling alley, shoe stores and other retailers providing goods and services to those earning incomes from the factories. Support businesses also grew -- sawmills that provided the shooks for wooden cases that held the cans ready for shipment; transporters; boat builders; suppliers of condiments; all of which offered employment opportunities. Byproducts of the industry like fertilizer, pearl essence (herring scales), and fish oil also contributed to the local economy. During this time the smoked herring business prospered as well, with some sardine canneries even operating herring smokehouses.

American Can Company, Lubec, ca. 1935

Lubec Memorial Library

Aerial View of Lubec, 1947

Lubec Memorial Library

Following a period of decline during the Depression, World War II revitalized the industry with factories on both the east and west coasts working at capacity to supply the Army and Navy with three million, one-hundred can cases per year. Seven new factories were built in Lubec. With the end of the War demand for canned sardines decreased sharply and the overbuilt industry began to decline. By 1976 there were two factories operating in Lubec – R.J. Peacock Canning Company and Booth Fisheries. Connor Brothers, the last of Lubec’s factories, closed its doors in September of 2001.

According to Edith Comstock, “There were fewer herring and not enough workers. Young people were no longer interested in the business. It’s true that the work was dirty, noisy and smelly – we got used to the odor – but the wages were decent if you wanted to work. The work was there for whoever needed it. We women used to have a good time. It was hard work but we all knew one another; we were like a family.”

Lubec High School Band, Washington, D.C., 1965

Lubec Memorial Library

The booming economy brought by the sardine industry resulted in more tax revenue for the town. This, coupled with a series of federal grants during the 1970s, led to improvements to the infrastructure including upgrading of the water, electric and sewer systems and a new municipal building. This period of prosperity also led to the expansion and eventual consolidation of the Lubec school system. A successful community fund-raising campaign resulted in the construction of a new gymnasium to house the high school’s competitive sports teams and, in 1965, the Lubec High School Marching Band traveled to Washington D.C. to represent Maine in the Cherry Blossom Parade.

Lubec’s era of economic prosperity ended in the 1970s, signaled by the closing of American Can and all but two of the town’s sardine factories. By 1975 McCurdy Smokehouse was the only remaining business of its kind in the U.S. Now a museum, the site is on the National Register of Historic Places. As jobs were lost and once thriving businesses closed the town’s population continued to decline. Today Lubec’s population stands at 1,551.

Looking Forward

Despite economic challenges Lubec residents have frequently come together to provide assets such as a public library, community playground, the Regional Medical Center and school improvements.

In the wake of the sardine industry’s demise those fishermen who remained turned to the lobster, scallop, shellfish and urchin fishery. Salmon aquaculture has also grown in Lubec and Campobello waters. Gathering balsam fir tips for the manufacture of Christmas wreaths, cutting fire wood and raking blueberries offers seasonal employment.

Growth in the tourism industry provides opportunity for future economic development. The opening of the Roosevelt International Bridge linking Lubec and Campobello in 1962, as well as the establishment of West Quoddy State Park and other conservation areas have contributed to an increasing number of visitors to Lubec, lured by the area’s natural beauty and recreational opportunities. Many of these people have purchased second homes here, established businesses, or become residents of the town.

In 2011 Lubec will celebrate its bicentennial, marking 200 years of existence on the easternmost edge of America. The town has watched its fortunes, much as the Fundy tides, rise and fall as the abundance of herring and demand for sardines disappeared. Throughout its history Lubec’s citizens have; through hard work, resilience, ingenuity and neighborliness; met the challenges posed by geographic isolation, a sometimes harsh environment, and the vagaries of a fisheries-based economy. These strengths should sustain the town as it welcomes its third century.

Winter in LubecWinter view of Lubec, from the International Bridge. Photo courtesy of KodaYoda Enterprises, LLC.

Sources:

Adams, Frank P., “Notes on the Maritime History of Lubec Maine”, The American Neptune, Vol. XXIV, No. 1, January 1964.

Bangor Daily News, November 10, 1923.

Bangs, Carrie, “Klondike: The Gold from Sea Water Story Promoted by the Electrolytic Marine Salts Company at North Lubec, Maine”, Lubec Herald, December 1948 – March 1950.

Earll, R. Edward, The Coast of Maine and its Fisheries, for the 1880 U.S. Fish Commission 1887.

Ellis, Kathleen, Lignell, “In the Sardine Factory or Where Have All the Herring Gone?” Nor’Easter, Maine/New Hampshire Sea Grant, Fall/Winter 1997.

French, Hugh T., “Smokehouse: Last of a Breed”, Salt, No. 28, October, 1986.

Gilman, John, Canned: A History of the Sardine Industry, Part I, John Gilman, Deer Island, N.B., 2001.

Hawes, Edward L., “Cobscook Timescape”, Island Journal, Vol. 9, 1922.

Johnson, Ryerson & Lois, 200 Years of Lubec History 1776 – 1976, 1976.

Kilby, William Henry, Eastport and Passamaquoddy: A Collection of Historical and Biographical Sketches, originally published 1888, Border Historical Society, 2003.

Lawrence, E.M., “A History of Sardine Canning”, The Canning Trade, January, 1914.

“Lubec … 1800: A Century of Progress”, The Herald Magazine, December, 1899.

Lubec Herald, February 26, 1891.

Lubec Herald, October 28, 1898.

Lubec Herald, January 4, 1902.

Lubec Herald, March 6, 1902.

Lubec Herald, April 3, 1910.

Maine Sardine Industry History, 1875 – 2000, Compiled by James L. Warren, Brewer, ME., 2000.

McGregor, James, History of Washington Lodge No. 37, Free and Accepted Masons Lubec, Maine, E.W. Brown, James B. Neagle, Portland, 1892.

Multhopp, Jennifer, “They Called Us Herring Chokers”, Memories of Maine, July 2007.

O’Leary, Wayne M., Maine Sea Fisheries: The Rise and Fall of a Native Industry, 1830 – 1890, Northeastern University Press, Boston, 1996.

Royle, E.C., Pioneer, Patriot and Rebel: Louis Delesdernier, 1972.

Schad, Vicki Reynolds, More Early History of Lubec, Maine.

Smith, Joshua M., Borderland Smuggling: Patriots, Loyalists, and Illicit Trade in the Northeast, 1783-1820, 2006.

Toft, John D., “Some Historical Data on the Maine Sardine Industry”, Maine Sardine Industry History.

Varney, George A., A Gazetteer of the State of Maine, Boston: Russell, 1881.

“When Lubec Was Number Eight”, Lubec Herald articles transcribed by Vicki Reynolds Schad, (published during 1930s and 1940s).